What Is Breast Density, Why Does It Matter?

1. What is dense breast tissue? What are dense breasts?

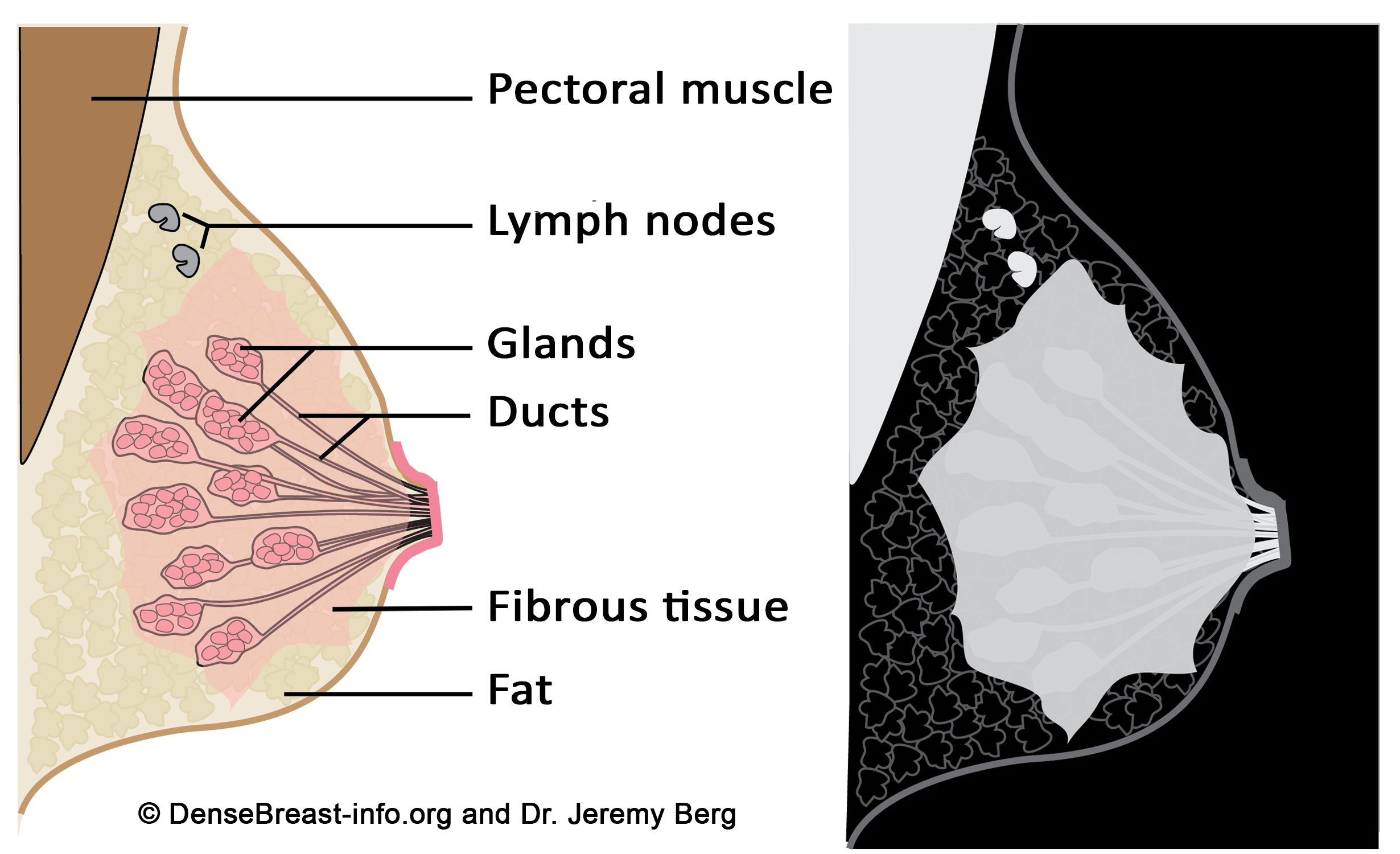

All breasts contain ducts, glands, fibrous tissue, and fat. Dense tissue is made of glands and fibrous tissue (“fibroglandular” tissue). Dense tissue blocks x-rays and therefore shows up as white on a mammogram. The muscle behind the breast, lymph nodes, and most other breast masses will also absorb x-rays and appear light gray or white on a mammogram, too. Fatty tissue allows more x-rays to penetrate and therefore shows up as black or dark gray on a mammogram. Each woman’s breasts are different than the next and contain a unique mix of fatty and dense tissue. Some women’s breasts are almost all fat, some have very little fat, and some are in between. Some dense breasts are mostly fibrous tissue and some are mostly glandular tissue. Dense breasts are normal and tend to become less dense with age and menopause. Breast density is not determined by how a breast looks or feels. Density is determined from a mammogram, either by a radiologist or by software.

Figure Diagrams of the normal breast. Left: The normal breast is composed of milk-producing glands at the ends of ducts that lead to the nipple. Varying amounts of fibrous tissue surround the glands. There is layer of fat just beneath the skin. Often a few lymph nodes and the underlying muscle are seen near the underarm (axilla). Right: On a mammogram, fat appears dark gray, glands and fibrous tissue (dense tissue) as well as muscle and lymph nodes appear light gray or white. Masses due to cancer also appear white.

2. Are lumpy breasts or fibrocystic breasts the same as dense breasts?

Having “lumpy” breasts doesn’t mean a patient has dense breasts, nor does it mean the breasts have fibrocystic changes. Both fatty and dense breasts can feel lumpy as the ligaments that support the breast can surround fat lobules and make them feel almost like soft grapes. Breast density is not determined by how a breast looks or feels but rather by the appearance on mammography.

3. How is breast density determined?

A woman’s breast density is usually determined during her mammogram by her radiologist by visual evaluation of the images taken. Breast density can also be measured from mammograms by computer software and it can be estimated on computed tomography (CT scan) and MRI imaging. In the U.S., information about breast density is usually included in a report sent from radiologist to the referring doctor after a mammogram. Breast density information may also be included in the patient letter sent after their mammogram. In Europe, national reporting guidelines to physicians vary; no country has a public policy for density reporting to patients.

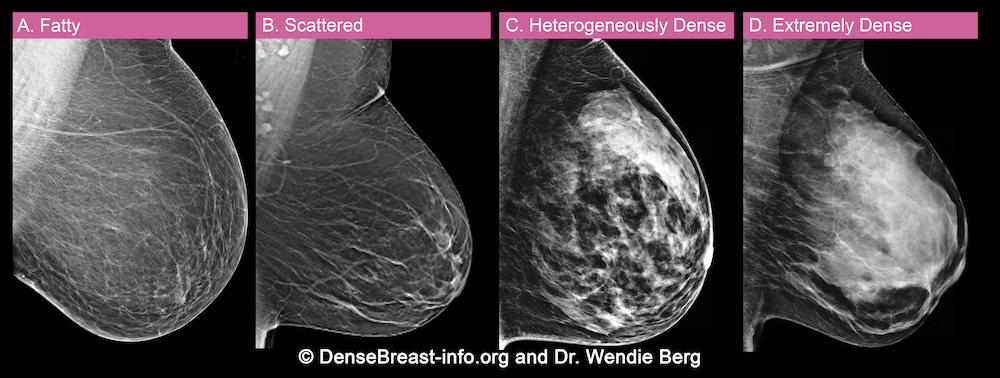

A woman’s breast tissue is categorized as one of four BI-RADS® [1] categories:

(A) Fatty; (B) Scattered fibroglandular tissue; (C) Heterogeneously dense; (D) Extremely dense

Breasts which are (C) heterogeneously dense, or (D) extremely dense, are considered “dense breasts.”

A. ALMOST ENTIRELY FATTY – On a mammogram, most of the tissue appears dark gray or black while small amounts of dense (or fibroglandular) tissue display as light grey or white.

About 10% of all women have breasts considered to be “fatty.”

B. SCATTERED FIBROGLANDULAR DENSITY – There are scattered areas of dense (fibroglandular) tissue mixed with fat. Even in breasts with scattered areas of breast tissue, cancers can sometimes be missed when they look like areas of normal tissue or are within an area of denser tissue.

About 40% of all women have breasts with scattered fibroglandular tissue.

C. HETEROGENEOUSLY DENSE – There are large portions of the breast where dense (fibroglandular) tissue could hide masses.

About 40% of all women have heterogeneously dense breasts.

D. EXTREMELY DENSE – Most of the breast appears to consist of dense (fibroglandular) tissue creating a “white out” situation, making it extremely difficult to see through.

About 10% of all women have extremely dense breasts.

References Cited

1. Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS mammography. In: ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology, 2013

4. Why does breast density matter on a mammogram?

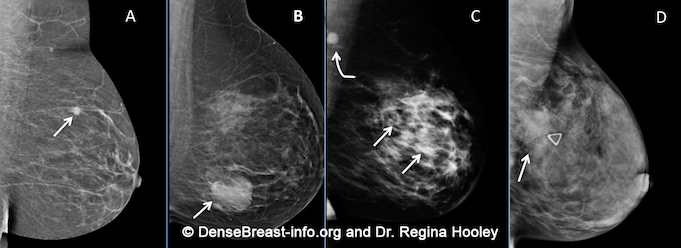

Cancers can be hidden or “masked” by dense tissue. On a mammogram, cancer is white. Normal dense tissue also appears white. If a cancer develops in an area of normal dense tissue, it can be harder or sometimes impossible to see it on the mammogram, like trying to see a snowman in a blizzard. If a cancer (white) develops in an area of fat (black or dark gray), it is usually easier to detect even when it is small. Because dense tissue can hide cancers, the more fatty a breast is, the more effective the mammogram is in showing the cancer. As breast density increases, the ability to see cancer on mammography decreases. The images below are examples of how cancer presents in each breast density category:

Mammographic Images Showing How Cancer Looks in Each of the Breast Density Categories. A) A small cancer (arrow) is easily seen in a fatty breast. B) In this breast with scattered fibroglandular density, a large cancer is easily seen (arrow) in the relatively fatty portion of the breast, though a small cancer could have been hidden by areas of normal dense tissue. C) In this heterogeneously dense breast, a 4 cm cancer (arrows) is hidden by the dense breast tissue. Note the metastatic node in the left axilla (curved arrow). D) In this extremely dense breast, a cancer is seen because part of it is located in the back of the breast where there is a small amount of dark fat making it easier to see (arrow and triangle marker indicating lump). If this cancer had been located near the nipple and completely surrounded by white (dense) tissue, it probably would not have been seen on mammography.

5. Do dense breasts affect the risk of developing breast cancer?

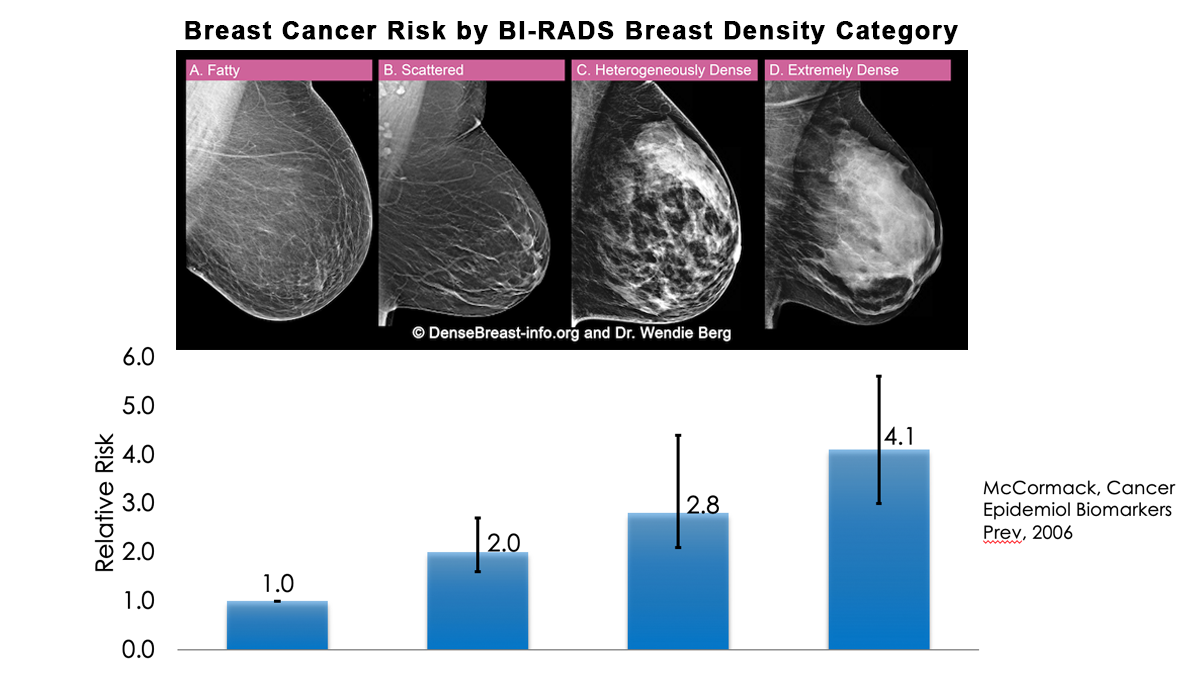

Yes. Dense breast tissue is a risk factor for the development of breast cancer: the denser the breast, the higher the risk [1]. A meta-analysis across many studies concluded that magnitude of risk increases with each increase in density category, and women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have a 4-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than do women with fatty breasts (category A), with upper limit of nearly 6-fold greater risk [2].

Most women do not have fatty breasts, however. More women have breasts with scattered fibroglandular density [3]. In some populations, denser breasts are more common. For example, Asian women are often reported to have denser breasts than do other races; however, after accounting for age at mammography and BMI, the differences are modest [4-6]. Women with heterogeneously dense breasts (category C) have about a 1.5-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than those with scattered fibroglandular density (category B), while women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have about a 2-fold greater risk.

There are probably several reasons that dense tissue increases breast cancer risk. One is that cancers arise microscopically in the glandular tissue. The more glandular tissue, the more susceptible tissue where cancer can develop. Glandular cells divide with hormonal stimulation throughout a woman’s lifetime, and each time a cell divides, “mistakes” can be made. An accumulation of mistakes can result in cancer. The more glandular the tissue, the greater the breast cancer risk. Women who have had breast reduction experience a reduced risk for breast cancer: thus, even a reduced absolute amount of glandular tissue reduces the risk for breast cancer. The second is that the local environment around the glands may produce certain growth hormones that stimulate cells to divide, and this is observed with fibrous breast tissue more than fatty breast tissue.

Risk for developing breast cancer is influenced by a combination of many different factors including age, family history of cancer (particularly breast and/or ovarian cancer), and prior atypical breast biopsies. Most women who develop breast cancer have no additional risk factors other than being female and aging.

Some risk factors can be influenced by behavior. Alcohol intake increases the risk of developing breast cancer, and the greater the intake, the greater the risk. Being overweight, especially after menopause, also increases the risk for breast cancer. Regular exercise reduces the risk of breast cancer.

There is currently no reliable way to fully know the interplay of breast density, family history, prior biopsy results, and other factors in determining overall risk. However, the largest study of its kind [7] found that dense breast tissue increases the risk of developing breast cancer more than family history, postmenopausal weight gain, or late childbearing.

For live links to breast cancer risk assessment tools click here.

References Cited

1. American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2019-2020.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2020.

2. McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15:1159-1169

3. Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:3830-3837

4. El-Bastawissi AY, White E, Mandelson MT, Taplin S. Variation in mammographic breast density by race. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(4):257-63

5. del Carmen MG, Hughes KS, Halpern E, Rafferty E, Kopans D, Parisky YR, Sardi A, Esserman L, Rust S, Michaelson J. Racial differences in mammographic breast density. Cancer. 2003;98(3):590-6

6. Habel LA, Capra AM, Oestreicher N, Greendale GA, Cauley JA, Bromberger J, Crandall CJ, Gold EB, Modugno F, Salane M, Quesenberry C, Sternfeld B. Mammographic density in a multiethnic cohort. Menopause. 2007;14(5):891-9

7.. Engmann NJ, Golmakani MK, Miglioretti DL, Sprague BL, Kerlikowske K. Population-attributable risk proportion of clinical risk factors for breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3:1228-1236

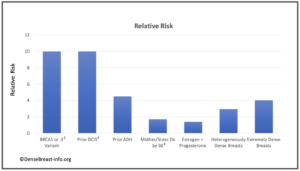

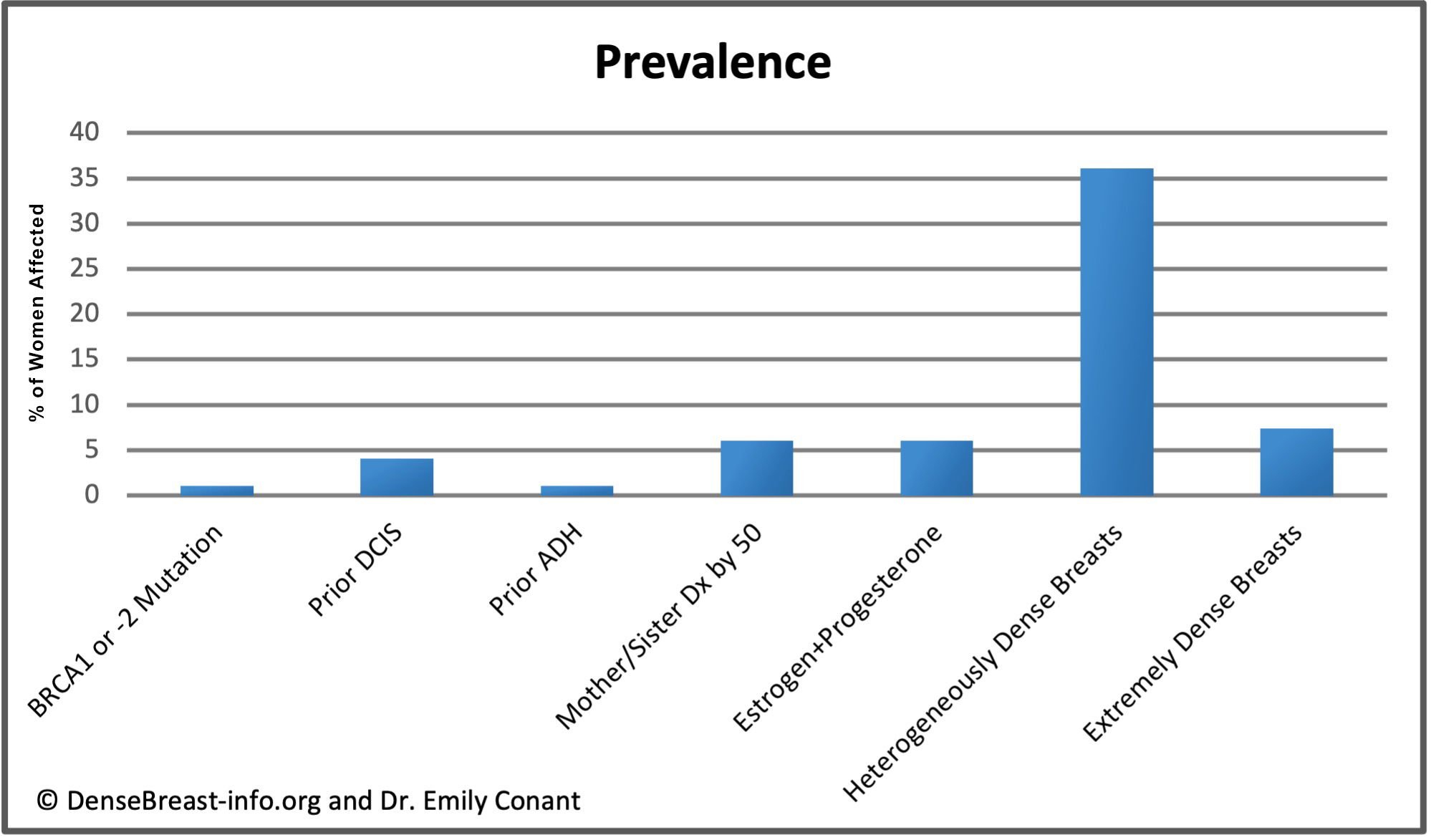

6. How does breast density compare to other risk factors for developing invasive breast cancer?

The charts below detail relative risk and prevalence [1-15].

Relative Risk: The top chart shows approximate relative risk of developing breast cancer by age 80 for a woman with a given risk factor compared to a woman without that risk factor: 1) disease-causing BRCA1 or -2 mutation [1-3]; 2) prior ductal carcinoma in situ [4-6]; 3) prior atypical ductal hyperplasia [7-9]; 4) mother or sister diagnosed with breast cancer by age 50 [10]; 5) combined estrogen and progesterone therapy after menopause [11]; 6) heterogeneously dense breast tissue (relative to a woman with fatty breasts) [12]; or 7) extremely dense breast tissue (relative to a woman with fatty breasts) [12].

1Average relative risk for BRCA1 or -2 mutations is about 10, varying widely from about 3-17 depending on study design and population studied [1-3].

2The 15-year risk of developing invasive breast cancer among women with untreated DCIS (i.e. found on retrospective review of surgical biopsy specimens years later) is about 10 times greater than the risk in the general population [4, 5]. The risk 3 years or more after DCIS diagnosis in women who receive standard treatment is nearly 3 times greater than the risk in the general population [6].

3 At any given age, risk associated with having a mother or sister diagnosed with breast cancer tends to be higher the younger the relative was at diagnosis, particularly for women under 50. For example, Data from nearly 160,000 women showed that in women under 40, relative risk was nearly 6 times greater if the relative was diagnosed before age 40, and nearly 3 times greater if the relative was diagnosed between age 40-50, than women without a family history in a first degree relative. In contrast, women 60 and older with a family history in a first degree relative have about a 40% increased risk regardless of the relative’s age at diagnosis [13].

Prevalence: The lower chart shows estimated prevalence of each risk factor in American women aged 40-74, except for hormone replacement therapy which applies only to postmenopausal women. Dense breast tissue is quite common, seen in 43% of all women aged 40-74.

References Cited

1. Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Pet al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017; 317(23):2402-2416

2. Kurian AW, Hughes E, Handorf EA, et al. Breast and Ovarian Cancer Penetrance Estimates Derived From Germline Multiple-Gene Sequencing Results in Women. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017; 1:1-12

3. Hu C, Hart SN, Gnanaolivu R, et al. A Population-Based Study of Genes Previously Implicated in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(5):440-451

4. Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Landenberger M. lntraductal carcinoma of the breast: follow-up after biopsy only. Cancer1982; 49: 75 1-758

5. Betsill WL Jr, Rosen PP, Lieberman PH, Robbins GF. Intraductal carcinoma: Long-term follow-up after treatment by biopsy alone. JAMA1978; 239:1863-1867

6. Mannu GS, Wang Z, Broggio J, et al. Invasive breast cancer and breast cancer mortality after ductal carcinoma in situ in women attending for breast screening in England, 1988-2014: population based observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1570

7. Worsham MJ, Abrams J, Raju U, et al. Breast cancer incidence in a cohort of women with benign breast disease from a multiethnic, primary health care population. Breast J. 2007; 13:115–21

8. Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:229–37

9. Hartmann LC, Radisky DC, Frost MH, et al. Understanding the premalignant potential of atypical hyperplasia through its natural history: a longitudinal cohort study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014; 7:211–7

10. Colditz GA, Kaphingst KA, Hankinson SE, Rosner B. Family history and risk of breast cancer: nurses’ health study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):1097-1104. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-1985-9

11. Schairer C, Lubin J, Troisi R, Sturgeon S, Brinton L, Hoover R. Menopausal estrogen and estrogen-progestin replacement therapy and breast cancer risk [published correction appears in JAMA 2000 Nov 22-29;284(20):2597]. JAMA. 2000;283(4):485-491

12. Cummings SR, Tice JA, Bauer S, et al. Prevention of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: Approaches to estimating and reducing risk. J Natl Cancer Inst2009; 101:384-398

13. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet. 2001; 358(9291):1389-1399

14. Couch FJ, DeShano ML, Blackwood MA, et al. BRCA1 mutations in women attending clinics that evaluate the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med1997; 336:1409-1415

15. Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst2014; 106