| QUICK FACTS |

*The exception is in patients under 30, and sometimes under 40, who may receive only an ultrasound for evaluation of symptoms. Any additional testing after a mammogram will find more things to be checked. Some may be cancer, but most will not (known as a false positive). To know whether a suspicious finding is cancer or not, further testing and possibly biopsy may be necessary. |

What is it?

Ultrasound uses high frequency sound waves that cannot be heard by humans, and does not use any x-rays (ionizing radiation). Screening ultrasound examinations can either be performed by hand by a trained technologist or radiologist who moves the probe (transducer) over the breast, or by using an “automated” or semi-automated system where the probe is operated by a motor with positioning assistance from a technologist.

Screening breast ultrasound, which scans the whole breast, can find some cancers that are not seen on a mammogram and may be an option for patients who are eligible for screening MRI but who cannot undergo, access, or tolerate MRI. Targeted (limited) ultrasound is used to evaluate a symptomatic area(s) (such as a lump), or an abnormality seen on mammography or other breast imaging exam.

Types of ultrasounds examinations

Handheld ultrasound (Fig. US-1) requires skill on the part of the technologist or radiologist performing the study to recognize when an abnormality is present and take images while scanning. The exam is done with the patient lying on their back. The axilla (area under the arm) may or may not be included as part of the exam. Following the examination, the images are interpreted and reported by the radiologist.

Automated breast ultrasound (Figs. US-2,3) imaging is done with the patient lying on their back using a wide (usually 15-cm) transducer and gentle pressure. At least three sweeps are made across each breast to image all of the breast tissue. Hundreds of images are acquired and reconstructed in three dimensions on a special workstation for the radiologist to review.

There are several other automated ultrasound imaging approaches. “Semi-automated” ultrasound uses the same smaller transducer as for handheld ultrasound, but the transducer is put in a motorized arm that moves across the breast in overlapping segments. In ultrasound “tomography,” the patient lies face down and lowers one breast at at time through an opening in a padded table into warm water. Each breast is then scanned by a ring-shaped transducer which moves up the breast.

On average, screening ultrasound takes about 15 minutes to perform, no matter which approach is used. When done by hand, the success of the examination depends on the ability of the person doing the scanning to recognize an abnormality and take good images of it. Skill in performing ultrasound varies. One advantage to scanning by hand is that additional images such as Doppler (showing blood flow) can be taken while scanning and a final recommendation can usually be made. When done by use of automated technique, screening ultrasound is less dependent on who performs the exam as the entire breast is imaged for later review. When an area of concern is seen on automated ultrasound, the patient will usually need to return for a targeted ultrasound done by hand in order to determine appropriate care.

How it works

Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to form an image. The sound waves pass through the breast and bounce back or “echo” to form a picture of the internal structures of the breast. Only gentle pressure is applied to the breasts and ultrasound rarely causes any significant discomfort. There is no ionizing radiation and no intravenous injection of contrast. A water-soluble gel or lotion is placed on the skin of the breast. The handheld or automated transducer directs the sound waves to the breast tissue to create a picture that can be seen on a computer screen.

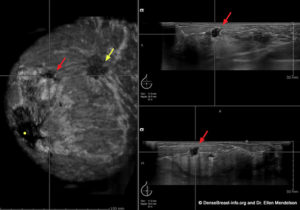

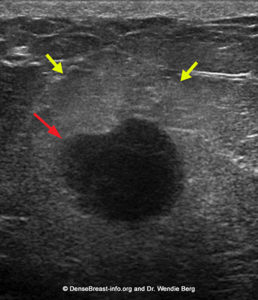

What does cancer look like on ultrasound?

Cancers usually present as masses that are slightly darker gray (“hypoechoic”) relative to the lighter gray fat or whiter (fibroglandular) breast tissue (Figs. US-4, 5). The specific shape (e.g. irregular) and margin (e.g., indistinct or spiculated) of the mass give the radiologist clues that a mass is more likely to be a cancer, rather than benign. Cancers can vary in appearance and if a mass does not appear definitively benign then the radiologist is likely to recommend a biopsy or follow up imaging.

Benefits

There are multiple benefits to screening ultrasound:

- Screening ultrasound can identify additional cancers not detected on screening mammography. If 1000 individuals with dense breasts have a screening ultrasound after a “normal” or “benign” mammogram, the ultrasound exam (handheld, automated, or semi-automated) will identify cancer in 2 to 3 individuals [1].

- More than 85% of cancers seen only on ultrasound are invasive, early stage, and node negative [1, 2]. These cancers are important to find as they can spread beyond the breast into lymph nodes and elsewhere in the body. Fortunately, most are found early enough on screening ultrasound to still be contained within the breast. Such cancers are treatable and patients typically have very good outcomes.

- Ultrasound is very good at detecting invasive lobular cancer, which is a type of cancer difficult to detect on mammography [1, 2].

- Screening ultrasound helps reduce the number of cancers found due to a lump or symptom between screening exams (known as “interval cancers”) [3].

- Ultrasound is readily available for diagnostic use, but not all centers offer screening ultrasound.

Considerations

Screening ultrasound does not replace mammography screening and is best paired with mammography, especially in patients with dense breasts. Some cancers may only be found on mammography, while other cancers may only be found on ultrasound.

In two multicenter prospective trials [3, 4], 20-30% of cancers were seen only on mammography and 29-33% of cancers were seen only on ultrasound. On average, ultrasound shows more areas that need follow-up/additional imaging than mammography. Some of those areas will be cancer, but the majority will not (known as “false positives”).

Other considerations:

- The false positive rate for either handheld or automated ultrasound ranges from 4-10% on the first exam (and is lower when there are prior comparison studies).

- Only about 10% of lesions recommended for biopsy via ultrasound prove to be cancer (known as “positive predictive value for biopsies”)[5].

- Semi-automated ultrasound detects at least as many cancers as handheld ultrasound, and produces fewer benign biopsies [6], but is not widely available.

- The benefit of adding screening ultrasound to 3D mammography (tomosynthesis) is less than when ultrasound is added to 2D mammography [7].

Of note, breast MRI is the most sensitive imaging modality available and there is no benefit to screening ultrasound if MRI is performed [4][8].

For information about breast imaging insurance laws by state, please visit our Legislation Map here.

Latest update 12/18/23

1. Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening breast ultrasound using hand-held or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging 2019; 1:283-296

2. Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol 2019; 29:1762-17770

3. Ohuchi N, Suzuki A, Sobue T, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of mammography and adjunctive ultrasonography to screen for breast cancer in the Japan Strategic Anti-cancer Randomized Trial (J-START): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387:341-348

4. Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA 2012; 307:1394-1404

5. Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening breast ultrasound using hand-held or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imag 2019; 1:283-296

6. Kelly KM, Dean J, Comulada WS, Lee SJ. Breast cancer detection using automated whole breast ultrasound and mammography in radiographically dense breasts. Eur Radiol 2010; 20:734-742

7. Berg WA, Zuley ML, Chang TS, et al. Prospective Multicenter Diagnostic Performance of Technologist-Performed Screening Breast Ultrasound After Tomosynthesis in Women With Dense Breasts (the DBTUST). J Clin Oncol 2023; 41:2416-2427

8. Berg WA. Data Do Not Support Semiannual Screening US after MRI, and Screening Mammography after MRI Has Limited Benefit. Radiology 2023; 307:e230932 (published online May 9, 2023)