If a Woman Has Dense Breasts, What Should Be Considered?

1. Does supplemental screening beyond mammography save lives?

Mammography is the only imaging screening modality that has been studied by multiple randomized controlled trials. Across those trials, mammography has been shown to reduce deaths due to breast cancer. The randomized trials that show a benefit from mammography are those in which mammography increased detection of invasive breast cancers before they spread to lymph nodes [1]. No randomized controlled trial has ever been performed on any other imaging screening modality and therefore there are no data showing that supplemental screening will or will not decrease mortality, though it is expected that other screening tests which increase detection of node-negative invasive breast cancers beyond mammography should further reduce breast cancer mortality.

Proving the mortality benefit of any supplemental screening modality would require a very large, very expensive randomized control trial with 15-20 years of follow-up. Given the speed of technological developments, any results would likely be obsolete by the trial’s conclusion. We do know that high-risk women having annual MRI screening are less likely to have advanced breast cancer than their counterparts who were not screened with MRI [2]. We also know that average-risk women who are screened with ultrasound in addition to mammography are unlikely to have palpable cancer in the interval between screens [3, 4] with the rates of such “interval cancers” similar to women with fatty breasts screened only with mammography. The cancers found only on MRI or ultrasound are mostly small invasive cancers (average size of about 1 cm), and the vast majority are node negative [5, 6]; MRI also finds some DCIS. These results suggest there is a benefit to finding additional cancers with supplemental screening, though it is certainly possible that, like mammography, some of the cancers found with supplemental screening are slow growing and may never cause a woman harm, even if left untreated.

References Cited

1. Smith RA, Duffy SW, Gabe R, Tabar L, Yen AM, Chen TH. The randomized trials of breast cancer screening: What have we learned? Radiol Clin North Am 2004; 42:793-806, v

2. Warner E, Hill K, Causer P, et al. Prospective study of breast cancer incidence in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation under surveillance with and without magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:1664-1669

3. Corsetti V, Houssami N, Ghirardi M, et al. Evidence of the effect of adjunct ultrasound screening in women with mammography-negative dense breasts: Interval breast cancers at 1 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer 2011; 47:1021-1026

4. Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA 2012; 307:1394-1404

5. Berg WA. Tailored supplemental screening for breast cancer: What now and what next? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 192:390-399

6. Brem RF, Lenihan MJ, Lieberman J, Torrente J. Screening breast ultrasound: Past, present, and future. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204:234-240

2. If my dense-breasted patient would like supplemental screening after her mammogram, how should I write the order?

Mammography using 3D/tomosynthesis is the preferred primary screening modality.

Availability of supplemental screening may depend on each practice. It can be useful to ask your local radiology facility what technologies are available.

To order supplemental screening for a woman with dense breasts, the ICD-10 code typically used as the indication for women with dense breasts is R92.2, inconclusive mammogram.

The order or “upfront permission” can be written as follows:

“Digital breast tomosynthesis/3D mammogram; screening [insert MRI, contrast-enhanced mammography or ultrasound here] due to dense breast tissue.”

For a woman with dense breasts or for those at high risk of developing breast cancer (regardless of breast density), breast MRI is the most effective supplemental screening test. The CPT code for bilateral contrast-enhanced MRI is 77049. Some facilities offer “abbreviated MRI” with direct-to-patient billing at a rate of $200-$600.

- For women unable or unwilling to have MRI, contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) or screening ultrasound can be considered. Though there is currently no specific CPT code for CEM, code 77066 (diagnostic mammography, both breasts) is often used. The complete breast ultrasound CPT code is 76641 and must be scheduled for each breast.

Patients often prefer to have all their breast screening done in one visit. This can be scheduled with the imaging center and would require “upfront permission” (prescription). Alternatively, MRI can be performed on an alternating 6-month schedule with a mammogram; computer modeling suggests this may be slightly more effective.

It may be possible to create a conditional, contingent order with the imaging facility or radiology department, indicating “additional testing permitted,” and/or to work with administration to add supplemental imaging to the electronic ordering system to facilitate scheduling. While supplemental dense breast screening with MRI detects more cancers than ultrasound, MRI may not be covered by insurance and is more often reserved for those women who are at high risk.

3. Should a routine annual mammogram for a woman with dense breasts be scheduled as a “diagnostic” or a “screening” mammogram?

Screening. “Diagnostic” mammography is monitored by the radiologist during the appointment and “screening” mammography is not. Indications for diagnostic mammography, rather than screening, include, but are not limited to, signs and symptoms of breast cancer such as a lump, bloody or spontaneous clear nipple discharge, skin or nipple retraction. If additional targeted imaging or follow-up is needed for an abnormality seen on the most recent prior breast imaging, a “diagnostic” appointment is also appropriate. In diagnostic breast imaging, additional views or ultrasound may be performed at the same visit if they are needed. The radiologist will interpret the breast imaging during the examination and the woman will leave with her results after a diagnostic mammogram. Women with a personal history of breast cancer can have their routine annual mammograms performed as diagnostic or screening examinations at many facilities. Diagnostic mammography is typically covered by insurance but subject to deductible and copay.

“Screening” mammography is fully covered by insurance under the Affordable Care Act for women over the age of 40 in the United States and may be covered for younger women, if recommended by her physician, depending on the insurance policy. Typically, screening mammograms are interpreted in a quiet, uninterrupted environment with the full benefit of prior examinations. Cancers are better detected and fewer unnecessary additional views (with associated radiation exposure) are recommended in the screening setting. Results are usually sent by mail to the patient within a few days to a week (by law not later than 30 days) after the appointment.

4. If a patient has dense breasts, what additional screening tests are available after a mammogram?

Depending on the patient’s age, risk level (for further explanation see section on Risk Assessment Tools) and breast density, additional screening tools, such as ultrasound or MRI, may be recommended in addition to mammography. The addition of another imaging tool after a mammogram will find more cancers than mammography/tomosynthesis alone (see Table: Summary of Cancer Detection Rates by Screening Method).

It is important to reassure the patient that it is normal for any screening test to find things that may need to be looked at more closely by use of additional testing. While some of these additional findings may be cancerous, the vast majority will not (this is known as a “false positive”); the only way to determine the importance of such findings is through additional imaging and sometimes biopsy.

Both 2D and 3D mammograms are x-ray technologies. X-rays have difficulty penetrating dense tissue and, as such, are more effective in fatty breasts than in extremely dense breasts. Early results suggest that ultrasound finds additional cancers hidden by dense tissue even after 3D mammography, though further study is warranted.

Ultrasound: Ultrasound is the only screening test suggested specifically for women with dense breasts as a supplement to mammography. In dense tissue, physician-performed or technologist-performed ultrasound has been shown to find an additional 2-4 cancers per 1000 women already screened by 2D or 3D/tomosynthesis mammography. Automated whole breast ultrasound, using special equipment, results in detection of another 2-3 cancers per 1000 women screened. Like all screening tools, ultrasound also detects many findings that are not cancer, but that may require follow-up imaging and/or biopsy. There is no x-ray radiation from ultrasound.

MRI: Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) can find the most breast cancers of any imaging test currently in widespread use. Breast MRI reveals an average of 10 additional cancers per 1000 women screened after mammography, even when both mammography and ultrasound have been performed. The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories.

A woman at very high risk for breast cancer (due to a known or suspected mutation in a breast cancer causing gene, or due to a greater than 20% lifetime risk for breast cancer according to the Claus, Tyrer-Cuzick, or other model that predicts risk for pathogenic BRCA mutation [1]) may be eligible to begin screening at age 25, or at least by age 30. In high-risk women, MRI is recommended annually, in addition to mammography, regardless of breast density, though before age 30 sometimes only MRI is performed due to the radiation sensitivity of younger breast tissue. Annual screening MRI is also recommended in women who have had prior radiation therapy to the chest at least 8 years earlier and before age 30, such as for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Recently, the American College of Radiology recommended annual screening MRI also in women with a personal history of breast cancer diagnosed by age 50, and in women diagnosed later who have dense breasts [2]. Annual supplemental screening MRI can also be considered in women who have a personal history of atypical or risk lesions, such as lobular carcinoma in situ.

MRI of the breasts requires intravenous injection of gadolinium-based contrast and lying in a tunnel-like space that may be difficult for women with claustrophobia. There is no x-ray radiation from MRI. Gadolinium has been shown to accumulate in parts of the brain, but no adverse effects have been shown from this.

MRIs have many false positives (when additional testing or biopsy is recommended for a finding which is not cancer). The benefits and risks of MRI in women who are not at high risk are being studied. In most centers, MRI is a very expensive imaging test that is not covered by insurance unless a woman meets high-risk definitions, and a copay and/or deductible may be incurred. MRI cannot be performed in women with poor kidney function, pacemakers, or certain other metal implants.

The addition of screening ultrasound is usually only recommended in women with dense breasts. Screening MRI is used in high-risk women of all breast densities. If screening MRI is performed, there is no need for screening ultrasound.

Screening MBI and Contrast-Enhanced Mammography may be offered to women with dense breasts or as an alternative to MRI at some centers. Further validation of such approaches is in progress.

References Cited

1. Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:75-89

2. Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Moy L, Niell B, Monsees B, Sickles EA. Breast cancer screening in women at higher-than-average risk: Recommendations from the ACR. J Am Coll Radiol 2018; 15:408-414

5. Will insurance cover supplemental screening beyond mammography?

In the U.S., the answer depends on the type of screening, patient’s insurance, risk factors, the state you practice in, and whether or not a law is in effect requiring insurance coverage for additional screening. In Illinois, for example, if ordered by a physician, a woman with dense breasts can receive an ultrasound without a copay or deductible. In New York as of January 1, 2017 all supplemental screening and diagnostic breast imaging are required to be fully covered (no copay/no deductible), though exceptions do exist. Generally, in other states, an ultrasound will be covered if ordered by a physician – but is subject to the copay and deductible of an individual health plan. In New Jersey, insurance coverage is provided for additional testing if a woman has extremely dense breasts. An MRI will generally be covered if the patient meets “high-risk” criteria*. In Michigan, at least one insurance company will cover a screening MRI for normal-risk women with dense breasts at a cost which matches the copay and deductible of a screening mammogram (which in most cases is zero). It is important for the patient to check with her insurance carrier prior to having an MRI. For insurance billing codes for additional breast screening, click here.

In Europe, national breast screening programs for women of average risk are offered free in nearly all European countries adhering to standards laid out in the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Variations do exist on the ages and risk factors of women invited to participate in routine screening, screening intervals, coverage and supplemental screening modalities utilized. Opportunistic mammography exists in some countries either as the sole screening system or in addition to the national breast screening program. Part of the cost is out of pocket payment or reimbursed by private insurance.

*For more information on high-risk criteria, see American Cancer Society guidelines: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html

6. What are insurance billing codes for supplemental (additional) breast screening tests after mammography?

- In the U.S.A., medical procedures are billed using both an ICD (International Classification of Disease) code and a CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) code.

- These codes can be used to check with an insurance company to learn if a specific test should be covered and what out-of-pocket costs (copay, deductible, or coinsurance) may be.

- Coverage varies by state and specific insurance plan.

Below are the insurance billing codes by breast imaging test. (Please note if additional breast imaging is needed because an abnormality is detected, that mammography/tomosynthesis is no longer considered “screening”, but instead it is “diagnostic,” and has different codes and insurance reimbursement. For ultrasound, MRI, and other breast imaging, CPT codes do not currently distinguish screening from diagnostic examinations.)

ICD CODE: For women with dense breasts, an appropriate ICD-10 code is R92.3 (which is “Mammographic density found on imaging of breast”). Note: other diagnosis codes may also apply based on medical history.

CPT CODES:

| Test | CPT Code | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 2D Mammogram (screening) | 77067 (both breasts, 2-views of each) | Code also includes computer-aided detection (CAD) when performed. The Affordable Care Act requires insurers to cover annual screening mammography beginning at age 40, without any out-of-pocket costs. For younger women at high risk, screening mammography typically requires a prescription from a physician and may be subject to out-of-pocket costs. |

| 2D Mammogram (diagnostic) | 77065 (one breast) 77066 (both breasts) | Codes also include computer-aided detection (CAD) when performed. Diagnostic mammography is typically subject to out-of-pocket costs. A diagnostic mammogram is monitored by the radiologist and should only be performed for patients with an appropriate indication such as a lump, nipple discharge, other symptom, or to further evaluate or follow-up abnormalities previously noted on breast imaging. Women with a personal history of cancer can have their routine annual mammogram performed as a diagnostic or a screening examination. |

| 3D Mammogram /tomosynthesis (screening) | 77067 (2D both breasts) + 77063 (3D both breasts ) | Most major insurers cover screening tomosynthesis; additionally, many states now require coverage. Out-of-pocket costs are possible. |

| 3D Mammogram /tomosynthesis (diagnostic) | 77065 (2D one breast) + 77061 (3D one breast) 77066 (2D both breasts) + 77062 (3D both breasts) G0279 – 3D (one or both breasts) if Medicare is primary insurance | Out-of-pocket costs usual. A diagnostic 3D mammogram is monitored by the radiologist and should only be performed for patients with an appropriate indication such as a lump, nipple discharge, other symptom, or to further evaluate or follow-up abnormalities previously noted on breast imaging. Women with a personal history of cancer can have their routine annual 3D mammogram performed as a diagnostic or a screening examination. |

| Contrast-enhanced Mammogram (CEM) | Currently no CPT code | Most CEM is done as part of research studies at this time. In centers offering clinical CEM, billing is often under CPT code 77065 (one breast) or 77066 (both breasts). Out-of-pocket costs usual. Some centers will also bill for the contrast and the contrast injection. |

| Ultrasound | 76641 (per breast) | When used for screening the “complete” breast ultrasound code will be billed for each breast, usually at half the rate for the second breast. Out-of-pocket costs usual in most states. A “limited” breast ultrasound, 76642, is used to evaluate abnormalities or particular areas of concern. |

| Molecular Breast Imaging, MBI | 78800 | Out-of-pocket costs usual. |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging, MRI (with contrast) | 77048 (one breast) 77049 (both breasts) | May require pre-authorization from the patient’s health provider. Out-of-pocket costs usual in most states. |

| Abbreviated MRI (with contrast) | Currently no CPT code unique to abbreviated MRI. The American College of Radiology endorses use of the modifier, “-52” (limited) exam, in combination with full protocol MRI CPT code 77049 (click HERE for more details, page 12). | Many centers will bill directly to the patient (range $200-$600). © DenseBreast-info.org |

Updated Nov 3, 2021. DenseBreast-info.org endeavors to provide up-to-date insurance codes; however, codes can change. These codes may not be the most recent version. No representations or warranties of any kind are made, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy or reliability of this information provided. A patient should always check with their specific insurance provider.

7. Does 3D mammography (tomosynthesis) solve the problem of screening dense breasts; is there a benefit to screening ultrasound after 3D?

Compared to standard digital mammography, 3D mammography (tomosynthesis) does improve the chance of finding cancer in most breasts. However, in women with extremely dense breasts, studies have shown mixed results as to whether 3D mammograms find more cancers than 2D mammograms. 3D does reduce the chance of having to return for additional diagnostic imaging for a false positive finding (false alarm).

Studies indicate there is benefit from screening ultrasound even after 3D mammography. Four large-scale studies [1-4] showed that ultrasound significantly improved detection of cancer even after the combination of 2D and 3D mammography in dense breasts. However, on average, ultrasound will also show more areas which need follow-up than does mammography. Some of those “finds” will be cancer, but the vast majority of these additional findings, determined after further imaging or biopsy, will be false positives.

References Cited

1. Tagliafico AS, Mariscotti G, Valdora F, et al. A prospective comparative trial of adjunct screening with tomosynthesis or ultrasound in women with mammography-negative dense breasts (ASTOUND-2). Eur J Cancer 2018; 104:39-46

2. Destounis S, Arieno A, Morgan R. Comparison of cancers detected by screening ultrasound and digital breast tomosynthesis. Abstract 3162. In: American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS). New Orleans, LA, 2017

3. Tagliafico AS, Calabrese M, Mariscotti G, et al. Adjunct screening with tomosynthesis or ultrasound in mammography-negative dense breasts (ASTOUND): Interim report of a prospective comparative trial. J Clin Oncol 2016

4. Dibble EH, Singer TM, Jimoh N, Baird GL, Lourenco AP. Dense breast ultrasound screening after digital mammography versus after digital breast tomosynthesis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2019; 213:1397-1402

8. If 3D mammography (tomosynthesis) is performed, will a patient also need a screening ultrasound or MRI?

If a patient has dense breasts, the answer is yes. In several large studies [1-4], including the ASTOUND [1] prospective multicenter trial in Italy, ultrasound significantly improved detection of cancer even after tomosynthesis (3D mammography) or the combination of 2D and 3D mammography in women with dense breasts. A 2020 prospective multicenter study [5] of abbreviated (“fast” or “mini”) MRI in 1444 women with dense breasts found an overall 3D mammography cancer detection rate of 6.2/1000 women screened vs. an overall abbreviated MRI cancer detection rate of 15.2/1000, a difference of 9/1000. If a patient has been recommended to have MRI screening because of her risk factors, she would still have MRI even if tomosynthesis is performed, regardless of her breast density. If screening MRI is performed, then screening ultrasound is not needed.

References Cited

1. Tagliafico AS, Calabrese M, Mariscotti G, et al. Adjunct screening with tomosynthesis or ultrasound in mammography-negative dense breasts (ASTOUND): Interim report of a prospective comparative trial. J Clin Oncol 2016

2. Tagliafico AS, Mariscotti G, Valdora F, et al. A prospective comparative trial of adjunct screening with tomosynthesis or ultrasound in women with mammography-negative dense breasts (ASTOUND-2). Eur J Cancer 2018; 104:39-46

3. Destounis S, Arieno A, Morgan R. Comparison of cancers detected by screening ultrasound and digital breast tomosynthesis. Abstract 3162. In: American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS). New Orleans, LA, 2017

4. Dibble EH, Singer TM, Jimoh N, Baird GL, Lourenco AP. Dense breast ultrasound screening after digital mammography versus after digital breast tomosynthesis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2019; 213:1397-1402

5. Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. Jama 2020; 323:746-756

9. How do I identify women who are at higher risk who should have MRI?

The American College of Radiology (ACR) [1] recommends all women, but especially Black women and women of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, undergo risk assessment and possible genetic testing by age 25 to identify those at higher risk who can then be counseled to begin earlier and more aggressive screening for breast cancer. All women benefit most from starting screening at least by age 40, and many women will meet current guidelines for supplemental screening MRI based on consideration of risk factors including age, mammographic breast density, family history of breast cancer, and breast biopsy history. Insurance coverage for screening MRI and risk criteria vary by state.

References Cited

1. Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Moy L, Lee CS, Destounis SV. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Higher-Than-Average Risk: Updated Recommendations From the ACR. J Am Coll Radiol. 2023 Sep;20(9):902-914

10. Is gadolinium contrast used in MRI imaging safe?

Gadolinium, a heavy metal, is injected intravenously as a contrast agent to help see breast cancer on MRI examinations. Most of the gadolinium is cleared by the kidneys. There are data showing that small amounts of gadolinium can accumulate in parts of the brain, especially after multiple MRI examinations. The importance of this finding is unknown and has not been linked to any known negative health effects in patients with normal kidney function. There appears to be more gadolinium retained by the body with certain types of contrast agents (so-called “linear” compounds) than with those that are more like a cage around the gadolinium (so-called “macrocyclic” compounds). When kidney function is less than normal, the dose of contrast used may be reduced. Gadolinium contrast should not be used in a patient who is pregnant or who may be pregnant. The Food and Drug Administration has concluded that the benefit of all approved gadolinium-based contrast agents far outweighs any hypothetical risks. Experts on our Medical Advisory Board agree, and we continue to recommend annual contrast-enhanced MRI for women at high risk. For further information, please see: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm589213.htm.

11. If recommended to have additional screening with ultrasound or MRI, will a patient need to have that every year?

Usually the answer is yes, though age and other medical conditions will change a patient’s personal risk and benefit considerations and therefore screening recommendations may change from one year to the next. Technology is changing and guidelines also evolve which influence recommendations.

12. Is MBI recommended for screening dense breasts?

Molecular Breast Imaging (MBI) is a specialized nuclear medicine breast imaging technique that requires intravenous injection of a radiopharmaceutical, typically 99mTc-sestamibi. Sestamibi has been in common use as a tracer for nuclear cardiology studies for over 30 years and has an extremely low risk of adverse reactions and no contraindications. Low-dose molecular breast imaging has been used with excellent results by Mayo Clinic and a few other centers for screening women with dense breasts, showing another 7 to 8 cancers after a normal mammogram for every thousand women screened [1-3].

MBI can also be useful as a diagnostic tool in women who have dense breasts and symptoms such as a lump or vague abnormality on mammography that in rare cases cannot be sorted out with additional views or ultrasound. MBI can also be helpful for some women who need but cannot have an MRI [4]. As of the most recent review in 2017, the American College of Radiology Practice Parameter for Molecular Breast Imaging [5] suggests MBI is a potential option for supplemental screening in high-risk women and those with dense breasts who cannot undergo MRI, but it is usually not indicated, as the technique involves ionizing radiation to the whole body with attendant risk of potentially inducing cancer [6]. MBI is never used in women who are pregnant.

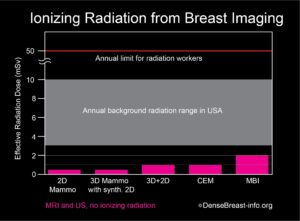

The radiation exposure from low-dose MBI, performed with a delivered dose of 6 to 8 mCi 99mTc-sestamibi, is higher than that from a mammogram. Further, mammography delivers radiation to the breast only, while MBI delivers radiation to the whole body. In order to compare radiation doses from these different types of exams, a standard calculation called “effective radiation dose” is used, which takes into account which body parts are exposed to radiation by a given test and how sensitive every exposed organ is to radiation. Effective dose has units of milli-Sieverts (mSv). The effective dose of mammography is about 0.5 mSv and the effective dose from a low-dose MBI is about 1.8 to 2.4 mSv. For comparison, the radiation dose received from normal daily life is between 3 and 10 mSv per year, depending on where you live [7, 8]. Below effective doses of 100 mSv, no health risks from radiation have been proven according to national and international radiation physics experts [9-11].

Chart 1. This graph shows the whole body effective radiation doses from common breast screening exams: 2D mammography; 3D (tomosynthesis) mammography with synthetic 2D; 2D combined with 3D mammography; contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM); and molecular breast imaging (MBI). MBI, with the highest dose, at 2 mSv, is below the range of annual background radiation exposure in the USA. The annual limit for radiation workers is 50 mSv. At doses below 100 mSv, no risks have been proven, and benefits to patients outweigh any possible risks. Any risk from radiation is greater in younger individuals, especially those under the age of 30, and radiation exposure should always be minimized (except when undergoing cancer treatment).

References Cited

1. Rhodes DJ, Hruska CB, Phillips SW, Whaley DH, O’Connor MK. Dedicated dual-head gamma imaging for breast cancer screening in women with mammographically dense breasts. Radiology2011; 258:106-118

2. Rhodes DJ, Hruska CB, Conners AL, et al. JOURNAL CLUB: Molecular breast imaging at reduced radiation dose for supplemental screening in mammographically dense breasts. AJR Am J Roentgenol2015; 204:241-251

3. Shermis RB, Wilson KD, Doyle MT, et al. Supplemental breast cancer screening with molecular breast imaging for women with dense breast tissue. AJR Am J Roentgenol2016:1-8

4. NCCN Guidelines. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis v.1.2023. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. June 19, 2023. Acessed August 3, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf

5. ACR practice parameter for the performance of molecular breast imaging (MBI) using a dedicated gamma camera. American College Of Radiology. Revised 2022. Accessed August 2, 2023. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/MBI.pdf

6. ACR appropriateness criteria: Breast cancer screening. American College Of Radiology. Revised 2017. Accessed August 2, 2023. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/70910/Narrative/

7. Radiation Sources and Doses. EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency. Updated February 16, 2023. Accessed August 2, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/radiation/radiation-sources-and-doses

8. Biological Effects of Radiation Fact Sheet. United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. December 2004. Accessed August 2, 2023. https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0715/ML071570056.pdf

9. Radiation risk in perspective: Position statement of the Health Physics Society. Health Physics Society. January 1996. Updated February 2019. Accessed August 2, 2023. https://hps.org/documents/radiationrisk.pdf

10. AAPM position statement on radiation risks from medical imaging procedures, Policy number PS 4-A. American Association of Physicists in Medicine. April 10, 2018. Accessed August 2, 2023. https://www.aapm.org/org/policies/details.asp?id=318&type=PP¤t=true

11. Biological Mechanisms of radiation actions at low doses: A white paper to guide the Scientific Committee’s future programme of work. Radiation UNSCotEoA. 2012; Accessed August 2, 2023. https://www.unscear.org/docs/reports/Biological_mechanisms_WP_12-57831.pdf

13. Should thermography be used to screen dense breasts?

No. According to the FDA, “There is no valid scientific data to demonstrate that thermography devices, when used on their own or with another diagnostic test, are an effective screening tool for any medical condition including the early detection of breast cancer or other diseases and health conditions [1].”

Thermography is a non-invasive technique that uses infrared technology to detect both heat and blood flow patterns very near the skin’s surface. Although some large cancers can be seen, these are usually palpable and so thermography adds little. Thermography has a high “false negative” rate (when a test result indicates “no cancer” – though cancer is actually present), especially for small breast cancers, so it does not play a role in screening asymptomatic women. Thermography also has a high rate of “indeterminate” findings, which on additional diagnostic evaluation (mammography, ultrasound, MRI, follow-up observation, etc.) indicate no cancer is found. These often prompt a recommendation for short interval follow-up, which creates anxiety and additional cost to the woman.

References Cited

1. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns thermography should not be used in place of mammography to detect, diagnose, or screen for breast cancer: FDA Safety Communication. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/breast-cancer-screening-thermogram-no-substitute-mammogram Published February 25, 2019. Accessed May 18, 2020

14. Can the decision on supplemental screening this year be based on patient’s breast density last year?

The answer is essentially “yes”. At the population level, there is a tendency for slight decrease in breast density each year, and this tends to be more abrupt in the few years around menopause. One study [1] showed that only 7% of women who were considered not dense one year were classified as “dense” the following year; similarly 6% of women considered “dense” one year were classified as not dense the following year. For 87% of women, there was no change from one year to the next. Any difference that might affect the decision for supplemental screening would be between women considered to have heterogeneously dense or scattered fibroglandular density one year or the other, and radiologists may differ in this assessment even when there is no true change in the breasts. In a patient with breast density near the threshold, there are likely to be areas in the breast where cancer could be masked: it is not unreasonable to have had supplemental screening even if one’s breasts turn out to be slightly less dense this year.

References Cited

1. Cohen SL, Margolies LR, Schwager SJ, et al. Early discussion of breast density and supplemental breast cancer screening: Is it possible? Breast J 2014; 20:229-234

15. What is Dedicated Breast PET (Positron Emission Mammography, PEM)?

What is it?

Breast PET uses an injection of a short-lived radioactive sugar (18FDG) into the body to detect metabolically active lesions such as cancer. PET, or more often PET-CT, is commonly used to stage the whole body in patients with larger breast cancers or suspected recurrence. Newer technologies can provide detailed PET images of the breasts to assess local extent of breast cancer.

How it works

The radioactive sugar accumulates in cancer cells in the breast and emits high-energy positron radiation that is detected and analyzed. For one such system, the patient is seated and the breast is gently stabilized; positioning is otherwise like mammography (Fig. PET-1).

Benefits

Breast PET is generally considered a diagnostic test used to determine the extent of cancer within the breasts, and can be used as an alternative to breast MRI for that purpose [1, 2]. In women with newly diagnosed breast cancer being treated with chemotherapy prior to surgery, breast PET can also help monitor response to treatment. In addition, breast PET may help distinguish recurrence of cancer from scar in women who have been previously treated for breast cancer. Uncommonly, it can be used for problem solving (Fig. PET-3). It is a relatively new modality and not widely available.

Considerations

Breast PET exposes the patient to a moderately high whole body radiation dose and is not used for screening [3]. The very back part of the breast near the chest wall and the axillary lymph nodes are better evaluated with MRI.

References

1. Berg WA, Madsen KS, Schilling K, et al. Breast cancer: Comparative effectiveness of positron emission mammography and MR imaging in presurgical planning for the ipsilateral breast. Radiology 2011; 258:59-72

2. Narayanan D, Berg WA. Use of breast-specific PET scanners and comparison with MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2018; 26:265-272

3. Narayanan D, Berg WA. Dedicated breast gamma camera imaging and breast PET: Current status and future directions. PET Clin 2018; 13:363-381