What are dense breasts?

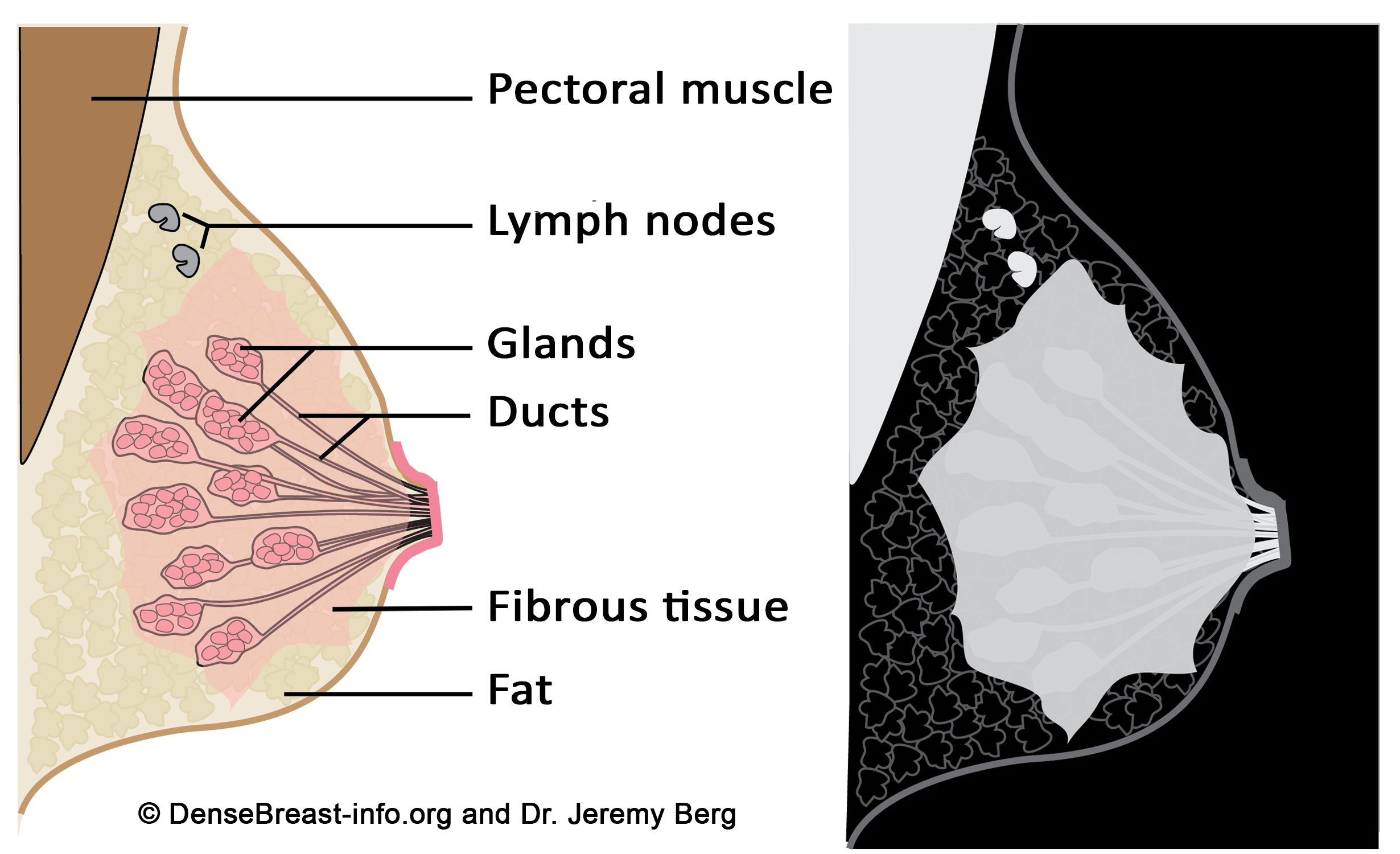

All breasts contain glandular tissue, consisting of the milk-producing TDLUs (terminal ductal lobular units) and major lactiferous ducts, fibrous tissue, and fat. Glandular and fibrous tissue (referred to as “fibroglandular” tissue) absorb x-rays and therefore show up white on a mammogram and are “radiodense” or simply “dense”. Fatty tissue allows more x-rays to penetrate and therefore shows up as dark gray (“radiolucent”) on a mammogram. No two women’s breasts are the same because each contains a unique mix of fatty and dense tissue. Some women’s breasts are almost all fatty, whereas others have varying proportions of fatty and fibroglandular tissue. As a woman ages, the proportion of fatty tissue gradually increases, so that by the age of 70 approximately 80% of all women will have mostly fatty breasts. Breast density is not determined by how a breast looks or feels but by how it looks on a mammogram.

Diagrams of the normal breast. Left: The normal breast is composed of milk-producing glands at the ends of ducts that lead to the nipple. Fibrous tissue surrounds the glands. There is layer of fat just beneath the skin. Often a few lymph nodes and the underlying muscle are seen near the underarm (axilla). Right: On a mammogram, fat appears dark gray, glands and fibrous tissue (dense tissue), as well as muscle, and lymph nodes appear light gray or white. Masses due to cancer also appear white.

If a patient has lumpy or fibrocystic breasts, are they “dense” breasts?

Having “lumpy” breasts doesn’t mean a patient has dense breasts, nor does it mean the breasts have fibrocystic changes. Both fatty and dense breasts can feel lumpy as the connective tissue that supports the breast can surround fat lobules and make them feel almost like soft grapes.

Fibrocystic breasts tend to be dense, but not all dense breasts have fibrocystic change. Fibrocystic change represents a spectrum of cyst formation, fibrosis, and “adenosis” (glandular proliferation). Fibrocystic change is more pronounced under the influence estrogen and progesterone, especially in perimenopausal women, and usually decreases after menopause. Fibrocystic breasts can appear dense due to cysts and/or areas of fibrosis (which resemble scar tissue). Cysts are very common and do not increase the risk for breast cancer; however, some other fibrocystic changes indicate active areas (“proliferative changes”) in the breast which do slightly increase risk for breast cancer.

How is a woman’s breast density determined?

A woman’s breast density is usually determined from the mammogram by her radiologist using visual evaluation of the images. Breast density can also be measured from mammograms using computer software and it can be estimated on computed tomography (CT scan) and MRI imaging. Information about breast density is usually included in the mammogram report sent by the radiologist to the referring doctor after a mammogram.

How is breast density categorized?

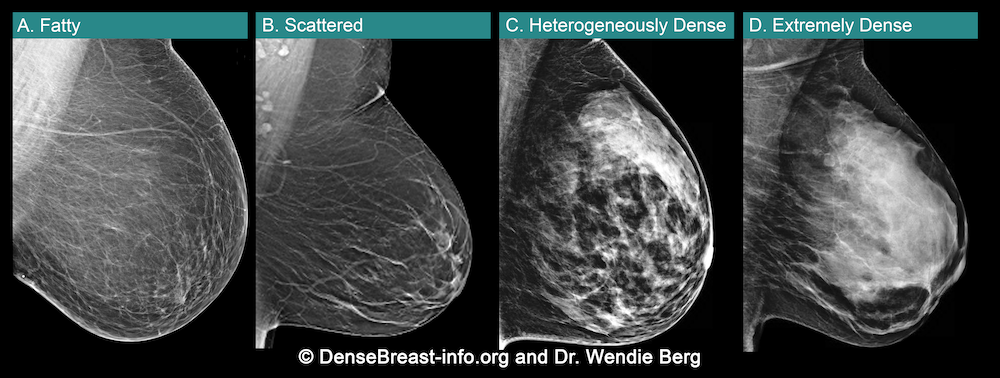

In the United States, a woman’s breast tissue is categorized as one of four BI-RADS® [1] categories:

A) Fatty; (B) Scattered fibroglandular tissue; (C) Heterogeneously dense; (D) Extremely dense.

Breasts which are (C) heterogeneously dense, or (D) extremely dense, are considered “dense breasts.”

A. ALMOST ENTIRELY FATTY – On a mammogram, most of the tissue appears dark gray or black while small amounts of dense (or fibroglandular) tissue and ligaments display as light grey or white. About 10% of all women have breasts considered to be “fatty.”

B. SCATTERED FIBROGLANDULAR DENSITY – There are scattered areas of dense (fibroglandular) tissue mixed with fat. Even in breasts with scattered areas of breast tissue, cancers can sometimes be missed when they look like areas of normal tissue or are within an area of denser tissue. About 40% of all women have breasts with scattered fibroglandular tissue.

C. HETEROGENEOUSLY DENSE – There are large portions of the breast where dense (fibroglandular) tissue could hide small masses. About 40% of all women have heterogeneously dense breasts.

D. EXTREMELY DENSE – Most of the breast appears to consist of dense (fibroglandular) tissue creating a “white out” situation, making it extremely difficult to see through. Extremely dense tissue lowers the sensitivity of mammography to detect cancers. About 10% of all women have extremely dense breasts.

Another method to classify breast tissue patterns is the Tabár system illustrated below and used in Sweden [2].

Figure illustrates patterns I (left) through V (right). In pattern I, shown here in a 48-year-old woman, there are concave ligaments and glandular tissue. This pattern tends to involute with age and is not associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer. Pattern II shows scattered fibroglandular elements, and is shown here in the same woman at age 51. Pattern III, in a 46-year-old woman, shows ducts and periductal supporting tissue behind the nipple. Patterns II and III also show no elevated risk of developing cancer and it is unlikely that cancer will be masked. In pattern IV, there is proliferation of the terminal duct lobular units, creating a nodular parenchymal pattern in this 63-year-old woman, and in V, the tissue is extremely dense in a 40-year-old. Pattern IV is associated with an approximately 2.4-fold increased risk of developing breast cancer compared to pattern I. Patterns I, IV, and V can mask cancer detection. About 12% of women undergoing screening mammography have pattern IV and 5-8% have pattern V.

- Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS® mammography. In: ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology, 2013

- Gram IT, Funkhouser E, Tabár L. The Tabár classification of mammographic parenchymal patterns. Eur J Radiol 1997; 24:131-136